Article from THE ECONOMIST

Urban planning

Streetwise

Cities are starting to put pedestrians and cyclists before motorists. That makes them nicer—and healthier—to live in

Sep 5th 2015 | GURGAON | From the print edition

At 6am on a sweltering Sunday the centre of Gurgaon, a city in northern India, is abuzz. Children queue for free bicycles to ride on a 4km stretch of road that will be cordoned off from traffic for the next five hours. Teenagers pedal about, taking selfies; middle-aged men and women jog by. On a stage, a black-belt demonstrates karate; yoga practice is on a quieter patch down the street. Weaving through the crowd dispensing road-safety tips is a traffic cop with a majestic moustache.

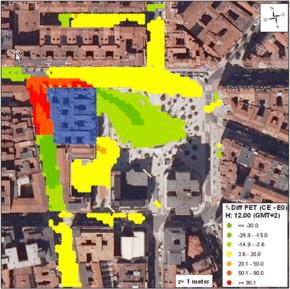

Gurgaon’s weekly jamboree is called Raahgiri (“reclaim your streets”). Amit Bhatt of EMBARQ, a green think-tank, started it in 2013, inspired by Bogotá’s ciclovía, pictured above, for which Colombia’s capital closes 120km of streets on Sundays and holidays. Such events are part of a movement that is accelerating around the world.

From Guangzhou to Brussels to Chicago, cities are shifting their attention from keeping cars moving to making it easier to walk, cycle and play on their streets. Some central roads are being converted into pedestrian promenades, others flanked with cycle lanes. Speed limits are being slashed. More than 700 cities in 50 countries now have bike-share schemes; the number has grown by about half in the past three years.

Cyclists and motorists have never liked sharing the road. In “A Cool and Logical Analysis of the Bicycle Menace”, P.J. O’Rourke, a car-loving comic, grumbles that “one cannot drive around a curve” without meeting a “suicidal phalanx” of “huffing bicyclers”. Casey Neistat, a New York cyclist who was fined $50 for not riding in a bike lane, made a film of himself crashing into some of the unkindly parked cars that so often make that impossible.

Many cities are exploring ways to keep petrolheads and pedalophiles apart. Over 100, particularly in Latin America, close some roads to cars on weekends. Paris is leading the way in Europe, closing over 30km; Dublin and Milan plan to banish cars from their centres. Even Los Angeles (a city Steve Martin, a comic actor, satirised by getting in his car to drive three paces to his neighbour’s house in “LA Story”) recently announced plans for hundreds of miles of bus and cycle lanes.

In the rich world, these measures follow improvements in public transport—and congestion charges and other policies that make driving and parking in many cities a misery. The number of cars entering central London has dropped by a third since 2002. Three-fifths of Parisians owned a car in 2001; now two-fifths do. And some people are shifting from public transport to walking or cycling: a fifth as many journeys in London are now made by bike as on the Underground; 15 years ago, only a tenth were. All this makes cities safer and nicer, planners say. London hopes to attract footloose talent this way, says Isabel Dedring, its deputy mayor for transport.

The International Transport Forum, a think-tank, predicts that by 2050 the world’s roads will have to cope with 2.5 billion cars and light trucks, three times as many as today. Almost all the growth will be in developing countries. Some cities are building rail and subway systems; others are creating rapid-bus lanes. India plans to expand or launch rapid transit in 50 cities. But safety is often neglected.

The best way to get more people walking is to slow down traffic citywide, says Guillermo Peñalosa of 8 80 Cities, a Canadian lobby group. Slower traffic makes neighbourhoods quieter and safer. More than 80% of pedestrians hit by cars moving at 65kph die; at half that speed only 5% die. A 25mph (40kph) speed limit went into effect in New York last year. London recently cut the speed limit to 20mph on more than 280km of its roads and is getting rid of pedestrian-unfriendly giant roundabouts. In September Toronto will slow down traffic on more than 300km of its roads.

Four wheels bad, two wheels good

In cycling, Amsterdam and Copenhagen are the pacesetters, with a third of trips made by bicycle. More than half of Amsterdam’s residents use their bikes daily. London, New York and Paris all have plans to challenge them. All three cities are expanding their bike-share schemes and building new bike lanes, some on quiet roads with new, lower speed limits for cars, and others running through central areas and separated from motorised traffic.

Such schemes can quickly convince more people to start pedalling. They are particularly popular with women, who transport planners say are more nervous than men about sharing roads with roaring traffic and typically make up less than a quarter of urban cyclists. In 2007-2010 the Spanish city of Seville built an 80km network of separated two-way bicycle lanes; the share of trips in the city that were by bicycle went from nearly zero to 7%. In Taipei few women cycled before its YouBike share scheme started in 2009; now they are half of the city’s cyclists.

Bike-shares are spreading out beyond city centres and being linked with public transport, says Kevin Mayne of the European Cyclists’ Federation. In Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands some schemes are run by the railways. More than 100 cities have smartphone apps that show which docking stations have bicycles available. Riders of Copenhagen’s GoBike can plot routes and check travel bookings from an on-board GPS. Both bikes and public transport are more likely to be used when bike racks are placed on the front of buses, as in Boston and Washington, DC, and secure parking is provided at rail stations.

In 2014 Britain’s transport ministry looked at recently built cycling and walking infrastructure in eight cities. Standard cost-benefit analyses for planned transport infrastructure include a value for the lives saved (or lost) through changes in the number of accidents. Using the same figures for the lives prolonged by increased activity, it found that the cost of the schemes was repaid three-fold—and again in reduced congestion. London’s authorities calculate that if every Londoner switched to walking for trips under 2km, and to cycling for trips of 2-8km, the share who got enough exercise to remain healthy simply by getting around would rise from 25% to 60%. That would amount to 61,500 years of healthy life gained each year.

Even once-a-week exercise fiestas can boost health. A 2009 survey of participants in Bogotá’s Sunday ciclovías found that 42% of adults did as much exercise during the event as the World Health Organisation recommends for a week. (It ranks Colombia the world’s most sedentary country: see article.) Only 12% would have done so otherwise.

Yet the health gains from walking and cycling rarely feature in transport plans—partly because the benefits are reaped by national health ministries (and the people who get fitter, of course), rather than the cities that build the infrastructure. Britain is trying to align incentives better. Last year London’s transport authority published a “transport health action plan”: a ten-year scheme, backed by £4 billion of government money, that will redesign streets along lines recommended by public-health experts. And the country’s National Health Service (NHS) wants to help cities that are building cheap housing complexes to include health-promoting features, such as cycle routes and playgrounds.

As rich cities are, at last, undoing their past planning mistakes, activists in developing ones are trying to ensure that they are not repeated. They are lobbying for safe walking and cycling routes as well as better public transport, and for traffic laws to be enforced—before pollution and inactivity take their full toll. Convincing officials preoccupied with keeping cars moving can be tough: “This won’t work here,” one told Mr Bhatt when he proposed the Raahgiri and other ways to make Gurgaon’s streets more pedestrian-friendly. He persisted, getting 200 schoolchildren to cycle up to the city administration’s headquarters to demonstrate public support. His team has since also convinced the city to paint cycling lanes at the side of some streets; barriers will soon protect them from cars.

One user is Dilip Grover, a 62-year-old manager of a small firm. Not having cycled since college, he rediscovered its joys after hopping on a free bike at the Raahgiri. He now cycles 10km to work. The Raahgiri has changed attitudes, he thinks: many drivers also participate and now think twice before honking at a pedestrian or jumping a traffic light. It is a small start.

From the print edition: International

ONLINE LINK